is under the bed,

first drawer, on the right.

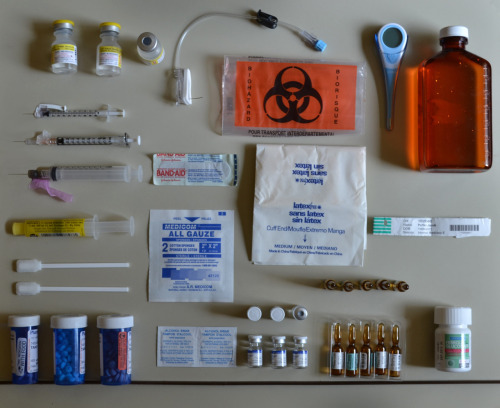

There are three catheters;

a dozen night bags;

a box of leg bags

a handful of flip-flos;

an abundance of G straps and leg straps;

Dressing Packs; Mepore; saline solution;

more than enough empty syringes;

Instillagel; barrier cream, Betnovate ointment,

Gabapentin; and a blue plastic Night Bag stand.

Bladder Washes are under the table,

next to the patient’s copious Notes.

Update in triplicate, please.

In case of emergency

If all hell breaks loose.

It happens.

In the morning, before we get up

the two litre drainage bag comes off.

Carry it carefully to the loo, and empty.

Use the special bin marked Clinical Waste.

Wash your hands. And before. Obviously.

Sorry. Teaching my granny how to suck eggs.

Force of habit – 40 years come this June.

Bladder Wash days are Mondays,

Wednesdays and Fridays. Before

our first cup of tea. Less mess. Trust me.

After our bath we’ll need a new G-strap

on our right thigh; and yesterday’s leg straps –

unless it’s change-over day. Every Thursday.

Twice a year we see the consultant. He only smiles,

like a little Buddha; repeats the same old, same old,

“I’m sorry, there’s no cure.” I mean. What is the point?

© Sophia Roberts

All rights reserved